The Rediff Special/Josy Joseph

At one time, Mohammed Iqbal Gundru of the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front was a hero. Those were the days when insurgency was just raising its head in the Kashmir Valley and the anti-India movement was beginning to turn violent. Gundru's big moment, though, came with the kidnap of Rubaiya, daughter of India's then home minister, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed.

To secure her release, the government gave into the militants' demands -- five of their jailed colleagues were released. That incident became a landmark in Kashmir's insurgency.

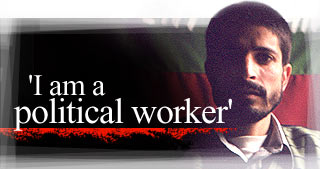

"We had struggled in a democratic manner for over 40 years, but there was no result. We wanted to focus the world's attention on Kashmir, so we deliberately decided to take to arms. And we were successful," says 32-year-old Gundru, who was released from jail this February after almost 11 years.

Others like him sit around in the JKLF office, which is located in the crowded, volatile locality of Maisuma, and talk of an independent Kashmir. They are the survivors of the generation that crossed the borders into Pakistan for arms training and returned to join the insurgency in Kashmir. Their words are still energetic, but their expressions fail at times -- the long years in jail have taken their toll, though not their pride at the events of the past.

For Gundru, as for the others, Time has changed. Many of the people he knew -- including Hilal Ahmed Baig and Mukhtar Ahmed Khan, who had accompanied him for training in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir -- are no longer alive. Baig, who had left the JKLF for the Islamic Front, died in 1996, allegedly in the custody of the J&K police's Special Task Force. "I was in Udhampur jail when I heard the news," recalls Gundru. In 1991, Khan was killed in a grenade explosion. He too had left JLKF, which was by then splintering into smaller groups.

The armed struggle Gundru and others like him sought to kick-start has undergone a complete change. "Now, it's the professional foreigners who are managing the show," he admits. "We declared ceasefire in 1994 and gave up arms. Now I am a political worker."

It is a struggle, though. Gundru and his compatriots, like Javed Ahmed Zargar (who was one of the five militants exchanged for Rubaiya) and Mohammed Rafiq Nannaji, are yet to establish themselves as legitimate political faces in Kashmir's struggle for freedom. "I was in Jammu jail after my arrest in August 1989. I was brought to Moti Lal's residence and released," Zargar recalls. Four months later, both he and Gundru were arrested. Zargar was paroled in June 2000.

It is a struggle, though. Gundru and his compatriots, like Javed Ahmed Zargar (who was one of the five militants exchanged for Rubaiya) and Mohammed Rafiq Nannaji, are yet to establish themselves as legitimate political faces in Kashmir's struggle for freedom. "I was in Jammu jail after my arrest in August 1989. I was brought to Moti Lal's residence and released," Zargar recalls. Four months later, both he and Gundru were arrested. Zargar was paroled in June 2000.

Today, they don't know if the people will accept them as political figures or whether their past will haunt their attempts at a new avatar. Several cases are pending against them -- including the Rubaiya case and the one where five Indian Air Force personnel were killed at the Rawalpura bus stop. Every month, the trio travels to Jammu, where the special TADA [Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act] court postpones their hearing to the next month.

"It is for the judiciary to decide if the cases against us should be dropped. We have already spent more time in jail than the maximum punishment we deserve," says Nannaji, who was one of the JKLF negotiators in the Rubaiya case. Arrested four months after her release, he was paroled in 1995.

Their story is the story of many of the youth in the Valley. The story of youngsters who took up a cause they passionately believed in -- Freedom! Gundru, for example, first held an AK-47 in August 1988. That was when he and other JKLF activists went underground to launch an armed struggle.

After some initial training, Gundru, Baig and Khan crossed over to PoK for further training. "It was a three-hour trek through Mandra [60 kilometres from Rajouri]," he recalls. There, they were trained to use the AK-47, light machine-gun, pistols and grenades. They returned a month later and Gundru joined other Pakistan-trained JKLF militants in the struggle.

Today, though, Gundru spends most of his time at the JKLF office. Manzoor Ahmed Sofi, who has returned after spending over 10 years in jail -- he was arrested for his involvement in both the Rubaiya and IAF cases -- sits next to him. After much prodding, he says feebly, "We are political workers now."

Over 10,000 JKLF activists have spent time in jail; 10 to 12 of them have actually been incarcerated for five to 11 years. Nannaji says there are many others like them, who have spent a good part of their youth in jails, but are now free. "Now, we are trying to organise ourselves as a political group. We are building ourselves at the grassroots," he says.

Does this mean the JKLF is losing its popularity? "What rubbish! People seem to acknowledge only the voice of violence." The militants-turned-politicians also complain that, despite the JKLF's 1994 ceasefire, its cadre continue to be killed. "We have lost about 350 people to the security forces." They blame the central government for delaying a resolution of the Kashmir problem. "This will only attract more and more foreign militants. Now that the Taleban have nearly finished their agenda in Afghanistan, they could turn their attention here."

Does this mean people like Gundru may once again adopt the path of violence? "That's all in the past," says Gundru. "Let's talk about the future."

Design: Dominic Xavier

The Rediff Specials